Some people inspire warmth, some attention, some compassion. The Johnstones inspired my immediate respect. Their focus alone was enough to make me sit up straight and get to the point quickly.

Once again, I was humbled at Afrikaans-speakers’ capacity to accommodate ill-equipped English speakers such as myself; at the outset, Mr Johnstone snr, Kobus, requested that we speak Afrikaans but after my first sentence, he conceded my complete lack of any ability and changed back to English. I can do many things but learning languages is not one of them. I suspect I was not paying attention when God was handing out language centres for our brains and he missed me completely. It’s a wonder I can even ‘English’.

| Date interviewed | 12 October 2018 |

| Date newsletter posted | 30 November 2018 |

| Farmers | Kobus and Bernard Johnstone |

| Mill | Pongola |

| Distance to the mill | Very close |

| Area under cane | 290 hectares |

| Tonnes to mill | 22 000 tonnes |

| Other income streams | Cattle, Contracting, Small investment in macs. |

| Cutting cycle | 12 months |

| Av Yield | 110 tonnes/hectare |

| Av RV | 12% |

| Varieties | N53, N57, N36, N41, N23 |

Kobus Johnstone is not from Pongola, he is a ‘Mafikizolo’. He explains that this means that he comes from the Amersfoort area. He grew up there, in a very conservative household. “In the 70’s, when you lived 30kms from town, you didn’t go in for anything. Everything was repaired on the farm and we didn’t have money for new equipment. It’s a very different way of operating.” They farmed cattle, maize, sheep and soya beans.

In 1994, Kobus sold the cattle farms (keeping some of the other land he had in Amersfoort) and bought a cane farm in Pongola. He had carefully considered the entire country when making this investment and decided that the water in Pongola was a real advantage. In the early 2000’s, once Bernard had completed his tertiary education at Lowveld Agricultural College, he settled in Pongola. Kobus had been splitting himself in two up until this point and decided to close the Amersfoort chapter and join his son. The Pongola farm did not have any buildings, so they lived in town. They bought a workshop in town where all their equipment and offices were based. One regret Kobus has is having sold all the Amersfoort properties – he would like to have kept an interest there as part of a more fully diversified portfolio.

I asked Bernard about his time at LAC and whether he thinks this type of academic training is valuable. “Practical experience equips you for the reality of running an agricultural operation better. You don’t necessarily have to get this experience on your own farm, it might be better to experience a different set up.” Kobus disagrees saying that someone fresh out of school needs to take time to settle into life and that studies are important. He understands that his son was impatient to get going though.

When they sold the Amersfoort farms, they already knew which new Pongola farm they wanted to invest in. It was a top performing, perfectly positioned farm, on the same road as their other farm. It was close to town AND it had homes on it. Despite failing to secure it a few times, they held out and, eventually, in 2016, at the height of the drought, they realised their dream. Although they have retained the workshop facilities in town, they now live on this farm.

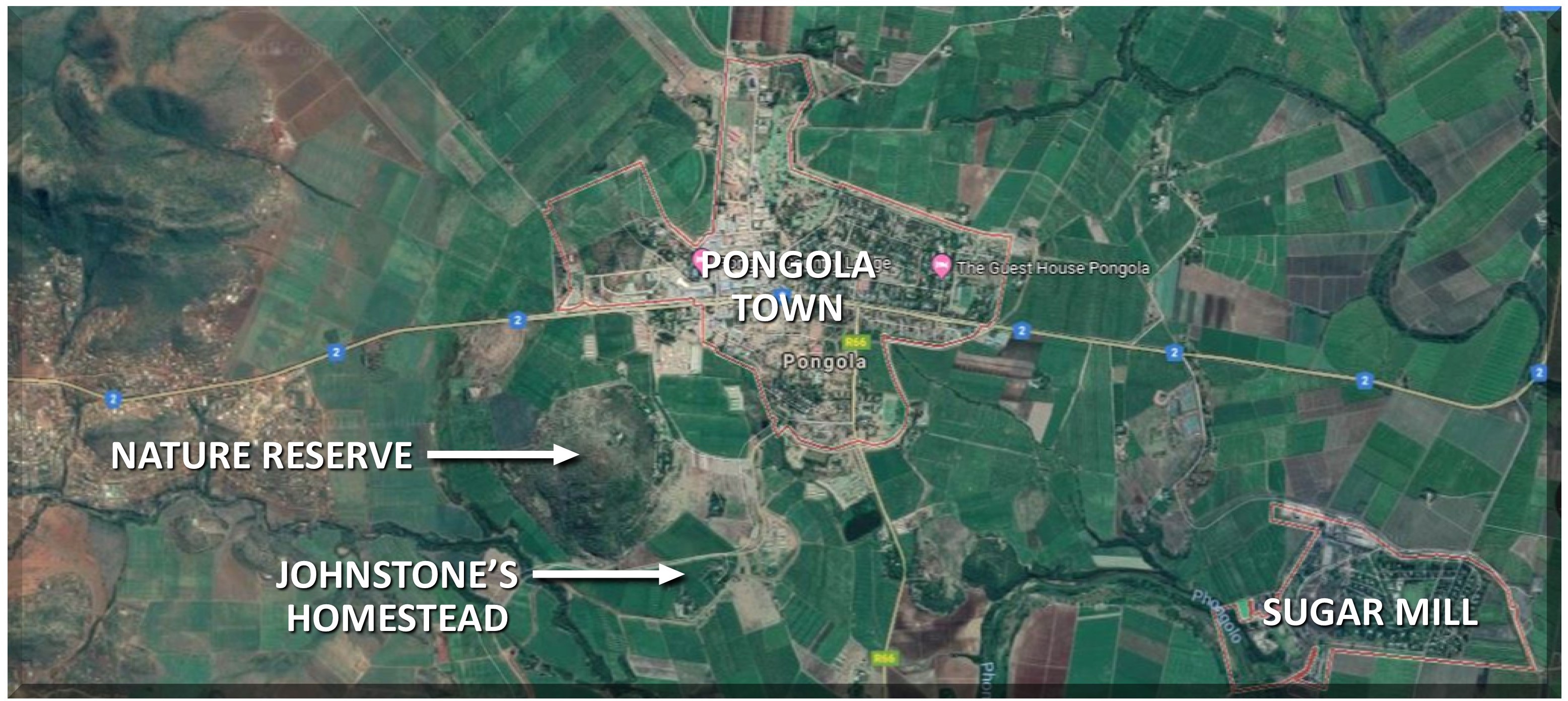

The picture below was taken from the top of the koppie in the Nature Reserve and shows the homestead on the plains below. The value the Johnstones saw in this unique property soon became clear to me.

Kobus had initially chosen Pongola because of the water and now he is faced with the worst drought in 100 years …

They humbly say that they really did not experience the drought as other Pongola farmers did and I have to agree with them when they say that God was looking out for them. Their yield did not dip below 100 tonnes/hectare. The lack of water forced them to carefully consider and plan the use of every drop. They even learnt how much they had over-irrigated pre-drought and realised the value of withdrawing water earlier from fields to be harvested; previously they had done this 6 weeks before but, in the drought, it had to happen as much as 3 months before harvest. This had a positive effect on RV and they have carried on withdrawing water early. It also taught them to place a higher priority on quality. Being so close to the mill, their default had always been to maximise quantity. All in all, the drought was more positive than negative.

It raised an interesting discussion about the trade-off between RV and yield so I decide to whip out the calculator and see how the equation works … seems that whether you produce 60t per hectare at 15% RV or 129t at 7%, your income will look the same.

| Quantity | Quality | Result |

| 60 | 15 | 9 |

| 64 | 14 | 8.96 |

| 69 | 13 | 8.97 |

| 75 | 12 | 9 |

| 82 | 11 | 9.02 |

| 90 | 10 | 9 |

| 100 | 9 | 9 |

| 113 | 8 | 9.04 |

| 129 | 7 | 9.03 |

Right now, they are looking at an average yield of 110t/h at an average RV of 12%. Their focus is firmly targeting lifting RV to at least 12,8% going forward.The opportunity to change your bank balance comes in when you include costs into the calculation; smaller cane is cheaper to harvest and transport, but the cane tends to produce highest sucrose when stressed and stressed cane becomes susceptible so maybe all those transport savings will be used on pesticides … It’s an interesting consideration though, and valuable to have two factors in play. Optimisation, rather than maximisation, becomes the goal. The Johnstones ended the 2016 season at 106t/h. Their norm prior to this had been 110t/h. Not only did they have far better RVs, they had also saved on electricity costs (less irrigation) and the soil was healthier as it had not been subjected to element-leaching over-irrigation.

To do this, they ripen everything. Their chemical of choice is Fusilade, without piggy-backing. Most farmers, employing a ripening programme in Pongola, piggy-back with a stronger chemical, closer to harvest to maximise the sucrose levels. With this comes an inflexible harvest date. The Johnstones have a unique situation that doesn’t allow for them to loose flexibility; they are contract harvesters who prioritise their customers’ businesses over their own harvesting. This means that their own fields are often left missing the ‘best date’. They will not compromise on service delivery for the harvesting business though and therefore will continue to search for other alternatives to chase that all important highest RV.

Here we see Kobus and Bernard with one of their customers, Mathe. While I was there, the harvesting teams were busy with Mathe’s fields. His community can be seen in the background. The great relationship and mutual respect was wonderful to witness.

Here we see Kobus and Bernard with one of their customers, Mathe. While I was there, the harvesting teams were busy with Mathe’s fields. His community can be seen in the background. The great relationship and mutual respect was wonderful to witness.

Besides contracting out their harvesting, transporting and ripening services, the Johnstones also prepare fields. Below we can see one of their impressive tractors ripping land due to be replanted.

Soil health

There are many focus areas in the Johnstone’s plan to elevate their farming – an important one is soil health. To this end, they have been investing in highly detailed soil analyses through Nulandis. This is literally a BOOK, per FIELD. Besides being incredibly interesting, it seems that the high price tag of these books is worth it – they’re about to harvest the first field to be treated ‘by the book’ and it’s looking very promising; it is obviously plant cane, N57, and Bernard is expecting a yield of about 140 tonnes / hectare. He says the first ratoon will be even better.

As you can see, this field is going to a harvesting challenge. The cane is so heavy that it cannot carry its own weight and most of the field has lodged. This also means that, despite the fact that irrigation has been withdrawn, the soil is retaining moisture under the blanket.

As you can see, this field is going to a harvesting challenge. The cane is so heavy that it cannot carry its own weight and most of the field has lodged. This also means that, despite the fact that irrigation has been withdrawn, the soil is retaining moisture under the blanket.

Rotation Crops

Before this field (featured above) was planted, they used cotton as a rotation crop. The advantages of cotton are:

- Roundup ready. Whenever a field is succumbing to kweek, they plant a crop that can withstand the chemicals required to eradicate the grass and still generate an income.

- Mechanical harvesting. Kobus prefers to avoid rotation crops that require hand-harvesting or are time-sensitive; they are simply too busy to accommodate these requirements.

- Price-stability. When you plant cotton, you can be fairly certain of the financial outcome, unlike veggies or other highly market-sensitive crops.

The other rotation crop they use is sugar beans. This has a shorter growing cycle – 3 months as opposed to cotton’s 7 months. As this extra time is precious, they will plant beans in fields that are not facing a kweek issue. Beans can also be mechanically harvested and stored and are relatively price-stable.

Last year, more than 10% of their 290 hectares was planted to a rotation crop. This year, as none of the fields have delivered less than 100t/h, there will be no plough-outs.

My assumption is always that the remaining organic matter will be incorporated back into the soil but that isn’t the case here … not this soil anyway. Meet the new favourite child: 7 hectares of macadamias. This is who’s getting all those juicy bits and pieces. I have to admit though, that the soil those poor macs are trying to grow in definitely needs the organic supplement.

The macs are 2-year-old Beaumonts and have been planted in marginal soils that simply could not support a decent sugar cane crop.

The macs are 2-year-old Beaumonts and have been planted in marginal soils that simply could not support a decent sugar cane crop.

Land Prep

As mentioned, Kweek is a big problem. Besides spraying a lot of Roundup, they also plough. This turns the kweek stool over and doubles their chances of killing it. As minimum tillage practices gain popularity, this is not a common farming practice anymore. But the Johnstones plough twice in the lead-up to replanting cane; once before the rotation crop and again after that crop has been harvested. Although the ploughing is expensive, (extra diesel and demand on the equipment) Bernard believes it is a significant reason behind their success. He has seen the difference in the 2 to 3 years since they have been doing it consistently. Kobus is not so sure; he has concerns about the compact layer created at the heel of the plough. For this reason, they also rip the field. This rip goes deeper than the plough and helps to relieve the undesirable side-effect. Besides all this, they also disc the soil, usually twice, creating a nice fine seedbed.

Planting and fertilising

Once the soil is fully aerated and free of the dreaded kweek, they draw ridges and put down fertiliser in one pass. They were using MAP fertiliser but have recently changed to an organic source of this phosphorous-rich supplement: chicken litter. This is purchased in pellet form and is more or less equivalent to MAP in both price and content. As they are trying to steer towards a more natural, organic form of farming, the chicken litter is preferred. They haven’t noticed a difference in results but can confirm that things definitely haven’t deteriorated since they changed over.

As soon as the fertiliser is in, they place whole sticks into the furrow, only chopping when it is necessary in order to fit the whole stick into the furrow. This often happens with the N57 that tends to produce rather ‘curly’ stalks. Placing whole sticks is unusual but both men insist that chopping is both time-consuming and unnecessary. If it is their own seed cane, they’ll place three or four sticks alongside each other in order to make sure they won’t have to come back to gap-fill. Because seed cane bought in is more expensive, they only place double-stick. I was intrigued to find out that the ideal age for seed cane is 9 months; young enough to still be growing actively and to have straighter stalks.

The only other element added during planting is Bandit which is sprayed on to combat Thrips. Then a ridge/roller comes through and closes the furrows, simultaneously pressing the soil down snugly. As Kobus likes nice smooth fields, the road roller will often come through and finish the job off. Thereafter, the field is drenched and left for 10 to 14 days.

Herbicides

About 3 to 4 weeks later, the weeds and cane would have emerged, with the weeds towering over the cane. The Gramoxone they spray at this point knocks everything back. When the next show happens, the cane will be larger than the weeds. They then spray with a Gramoxone-metribuzin mix.

Apart from these two applications, a permanent team of spot sprayers focus on field edges.

Fertilisers

First, we need to rewind to the penultimate harvest of a field when kraal manure is broadcast at a rate of 8 to 10 tonnes per hectare. They source this from the local feedlot where it has already been matured for about 4 years and is a dry powder. It is a part of an active focus to incorporate more organic matter into the soil.

The next stage of fertilising happens in planting, as discussed above when the chicken litter is placed in the furrow. When the cane is about 4 weeks old and just under knee-height, urea-based, coated 6:1:8 is applied at a rate of 400kgs per hectare. This is applied, mechanically, directly onto the base of the plant. 8:1:6 is a more common choice of fertiliser in Pongola but Kobus decided to change the formula when he read one of Bernard’s college books one day; he had always been a little unhappy with the ‘skinny’ cane sticks and the textbook explained that potassium helps with yield. Since then he has been using a 6:1:8 and is happy with the results. Nitrogen-heavy fertilisers produce a nice-looking, richly green field because nitrogen specifically helps leaves but, thick stalks are more important to Kobus. This situation highlighted a key to the Johnstones’ success; they are eager to learn, regardless of the fact that they are already highly experienced and successful.

Soil sample reports usually specify a shortage of calcitic lime so that is applied as a standard practice.

When it comes to ratoon cane, a split application of 6:1:8 is the norm. 400kgs/hectare immediately after harvest and the next 400kgs/hectare about 3 months later, which is the latest that the equipment can enter the field without damaging stalks.

At about 4 months, a high clearance tractor applies a little bit of nitrogen. This takes the total nitrogen input up to around 180-200kgs/hectare, over three applications.

Varieties

N57 & N53 make up 85% of the cane here. Both are performing very well. Kobus is not happy with the performance of N41 with its poor yields. The RV’s at certain times of the year are not bad but it cannot compete with the newer varieties. When they bought the farm, it had a few fields of fairly young N23. It is not a variety with which they had much experience but have not been disappointed in its performance thus far. N36 is still reliable and, in the interests of spreading risk, they are going to look for some N49 next year.

Irrigation

There are three types of irrigation used, each for a very specific reason:

- Centre pivots are the favourite because of how easy they are to manage – a simple drive past will give you comfort that all the nozzles are not blocked. They also allow large amounts of water to be applied in a shorter time. This was especially helpful during the drought when they would only get access to water for a week at a time. Having the centre pivots allowed them to immediately dump large quantities of water onto the thirsty fields. Had they been operating sprinklers, it would have been necessary to first fill the dams and then start the irrigation schedule, limiting the likelihood that all fields would be adequately irrigated before your week window closed. Centre pivots also require less labour. A disadvantage is that they regularly require an electrician to restart them after an extended period of inactivity, although Bernard is quickly learning how to deal with their issues in this regard. They also have constant theft of the motors but hopefully, after reading about how Delarey Meintjies (link to SB article on Delarey) attended to this issue, this will be solved.

- Semi-permanent. These are used in the ‘corners’ of the centre-pivot fields.

- A 50-hectare farm that the Johnstones lease from the municipality is literally across the road from the town centre, making equipment theft unmanageable. To address this, they have started using flood irrigation in the 6 hectares closest to town and the crop is responding remarkably well. Below, you can see the channel down which the water flows. It is directed down the rows when a good old spade is used to open the appropriate rows. If they want a quick, shallow burst, a few rows are opened. If they require a more deep, soaking job, they open more rows. The simplicity, affordability and results have all been amazing.

The only draw back is that the neighbouring field, which is irrigated by the centre pivot, might be receiving too much water. Bernard is watching the situation closely.

The only draw back is that the neighbouring field, which is irrigated by the centre pivot, might be receiving too much water. Bernard is watching the situation closely.

Once again, I am enthused by the positivity of these farmers as they take the good from a bad situation. They have now found a form of irrigation that has not only solved the theft problem but seems to be producing better results than the sprinklers that were here before. Now they need to find a way to address the wholesale theft of cane from these fields – about 200-300 sticks of cane are sold in town at R5 apiece. All of them come from this farm. When necessary, a security guard is placed here. Never thought I’d hear about cane requiring this kind of protection! And it seems these 2-legged pests are the only ones encountered by the Johnstones. They don’t have to worry about Eldana or any of the other common outlaws. They think it’s because most of their cane is only 4th or 5th ratoon.

In this picture, you can see how close this farm is to town.

In this picture, you can see how close this farm is to town.

The irrigation scheduling is done by instinct and manually checking the soil. They don’t have probes although they see this as another opportunity by which they can improve down the line, as soon as they have time to investigate.

Harvesting

One of the first things I noticed when arriving at the farm workshop was the harvestor.

Obviously intrigued, I couldn’t wait to hear the story behind it. When the Johnstone’s harvesting contracting business grew unexpectedly, they began to fall behind so the harvestor was purchased to address that issue. Turns out that the 40 (FORTY!!!) litres per hour it consumes coupled with its extremely limited manoeuvrability made it more of a hinderance than a help. Although it is still fully operational and was currently outside being serviced and maintained, its primary purpose now is as an “afskrikmiddel”. For my fellow Englishmen, that’s a friendly warning to the people that there are machines that can do their job. If you refer below, to the section on labour, you’ll see how keeping this machine might just have been a very wise decision.

The Pongola norm of cut, place in windrows and loading transport trucks in-field with a tri-wheeler is employed here. Although they are well-equipped for this modus operandi, they do acknowledge this is yet another area in which they can improve in as far as compaction concerns go. But with eight Bell loaders and numerous trucks, any changes will have to be carefully considered and planned.

The Johnstones burn in the evenings. The cutters prefer it because the ash has then settled by the time they access the field. Experience has proven to Kobus and Bernard that this does not affect the RV, although they know the mills disagree.

What does affect RV is correct cutting and focus is therefore placed on cutting low and topping accurately. The tops are left in the inter-rows and not burnt. There is organic value in this trash and they help to control the weeds – to such an extent that, if they had the time to fuss with this detail, they would restrict herbicide application to the ‘naked’ inter rows only.

Labour

Always a challenging department but particularly so this week. Bernard was arrested for employing an illegal immigrant. It was a spectacular event, complete with road closures, fire engines, multiple SAPS and Metro staff and vehicles … all for one man. He was loaded into the SAPS van and taken to the holding cells, charged and, later, released on bail. He has many months of red tape ahead of him and might end up with a fine and criminal record. The employee concerned was a Swazi who was employed by the mechanic at the workshop. Bernard had no idea he was a foreigner but admits that their busyness in running this large operation means that they simply don’t have the time to check everyone’s credentials personally. This one slipped through the cracks and now he must face the consequences. They have now had to send most of their cane-cutting workforce away until all their paperwork can be verified. This is obviously having an impact on the harvesting schedule … maybe the mechanical giant will come in handy …

Currently, the Indunas have complete control of staff, who they hire and for what jobs. This has removed some of the load off Kobus and Bernard but, besides the legal exposure, it is also very easy the trust to be abused. As with everything, it’s a trade-off.

Staff are well cared for with anyone who wants to, being put through their driver’s licence – this year alone they paid for the complete process and popped out 9 licenced drivers. They are also in the process of upgrading all staff accommodation. Besides that, they provide as many vegetable seedlings as a person wants. This secures a supplementary income for the staff who sell their produce. Even Minette, Bernard’s wife, buys her fresh veggies from her own farm.

Administration

Kobus and Bernard have absolutely nothing to do with any of the admin. They spend no time in the office at all. Minette is the boss here and has two ladies assisting her.

Diversification

- As mentioned above, the marginal soils are being planted to macs. Although Kobus and Bernard are still not entirely convinced this crop is what they should be getting into, they don’t want to be the only idiots not doing it (if that’s how the situation pans out) so their approach has been low-key. There are already 7 hectares in and plans for another 11 hectares are in the pipeline. Bernard says he won’t exceed 35 hectares, nor will he use any of his good soils. Despite this deliberate ‘side-lining’ and Bernard is very happy with their progress, especially considering that he has not had the capacity to attend any of the mac-related workshops or to learn too much about their cultivation. Kobus teases Bernard that, even though Bernard insists that he isn’t focused on the trees, he is actually spending a lot of time on them. He doesn’t begrudge him this time, he just points out that, when someone enjoys something as much as Bernard is enjoying the new orchards, they don’t realise how much time they are spending on it. It is probably also the intrigue of something new, especially with regards to the irrigation – they are using microjets.

With low expectation comes low disappointment so I hope that the Johnstones are wonderfully rewarded when the macs deliver above expectation, which won’t be hard given that they are not expecting much at all.

The fencing might seem overkill but it is also to protect the sheep that Minette has invested in. Their purpose is two-fold: keep the grass in check and realise a return at the auction.

- We have discussed this a little but it is interesting to note some issues unique to this department: Kobus explains that the customers only want to see big shiny machines so, although he loves his old machines, he doesn’t see them playing a role in their business now. Reliability is paramount. When equipping themselves, they look for the best service with quick responses to all issues. Lately they’ve been buying John Deere because they have a great new dealership in town and the service has been exemplary. Both the contract harvesting and haulage divisions are operated purely to supplement the cane farming business which is where their real passions lie.

- The Johnstones have 800 hectares of cattle farm. It is predominantly a Boran stud farm with 55 females plus bulls. This is supplemented by 200 commercial cattle. Kobus clearly has a soft spot for cattle but this is justified in many regards; they are great collateral and most banks will take cognisance of a valuable herd. They can also be used as a ‘stock market’ resource (excuse the pun) which is what they did in 2015. Kobus saw the potential for a drought and decided to sell the 200-strong herd while the price was high. He insists that, although this turned out to be a very wise decision when the drought intensified, it didn’t require great wisdom – simply sell your stock when the price is at its highest. If circumstances turn out the way you predicted, it was a good decision. If they don’t then you can always buy the stock back, and because you sold at a high, you’ll probably be able to buy the same number back at a lower price. He warns against getting sentimental with a herd – this lands many farmers in trouble. During a drought, money in the bank beats hungry beasts.

Balance

“To be a farmer, you have to love it. When you commit to it and make that investment you will find a way to pay the bills.” Kobus believes that nobody can really afford a farm but it’s an all-consuming passion that some people cannot escape. Once you are in it, it demands all your time and energy. These two men work 7 days a week, 365 days a year but they love it and wouldn’t change a thing. One of the things they have done to make one-hour holidays possible is to bring the Kruger to them. The koppie on the farm was fully fenced when they bought the property. It is too rocky and steep to use agriculturally so they have created a nature reserve in there. I was delighted when we ‘went on holiday’ to explore the 100-hectare retreat.

Some of our sightings

Some of our sightings

The kids recently acquired a few baby ostriches which are currently enjoying some mothering at the homestead but when they grow up, they be released into the reserve as well.

Wrapping it up

When I started this interview, I was nervous about such busy men having taken time out of their insanely busy days to tell me how they farm successfully. There was no personal return on this investment. But, as we progressed, I realised that, despite their all-business exteriors, these were two incredibly kind and generous men. Two other things struck me on this visit:

- The relationship between Kobus and Bernard is rare and precious. There is so much mutual respect and appreciation. Kobus says that Bernard is the best thing that ever happened to their business, “Young people come with new ideas that you are not comfortable with. But I decided to give him a chance. A lack of progress can lead to ruin, whereas new ways are often the only way to survive. If his (Bernard’s) ideas ran no risk of ruining the business, then I let him go ahead and it’s been the best thing for all of us. Youngsters have new, fresh ideas and older people need to give the youngsters a chance.”

- Their relationship with God. Supremely humble, they give all glory to God. They pray every day and ask Him for guidance.

I hope you all see the privilege and value that people like the Johnstones bring to our lives by sharing their wisdom and experience. On behalf of everyone I thank you both, sincerely, for the input and teaching; we look forward to seeing your continued growth and success.

And that’s it from Pongola. Our next edition is the final one for 2018 and we will continue to bring you enlightening, uplifting and inspiring articles from our industry experts in 2019.